The Climate Action Lab: Introduction

Kaja Kühl is an Urban Designer and Adjunct Associate Professor at Columbia GSAPP. She originally developed the Climate Action Lab as a week-long workshop to take place at Wally Farms. COVID-19 may have changed the format of this workshop, but it has also highlighted its relevance. Fundamental to climate action is the urgent need to rethink how humans build their homes and communities.

In lieu of an on-site workshop, Kaja will be sharing her curriculum digitally. Each article will explore an element of the research and design process, highlighting pragmatic solutions to the climate crisis. The series* is intended to spark conversation on how to ACT on climate solutions, and will ultimately offer a insights for creating carbon neutral dwellings and communities.

An Introduction

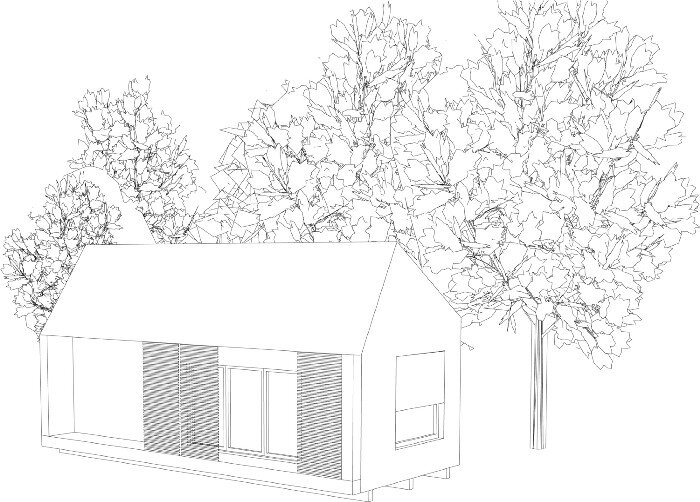

The Climate Action Lab is an experimental laboratory to explore architecture and urban design solutions that address the climate crisis. In early 2020, I started planning this project as an on-site workshop at Wally Farms, a research and teaching landscape in the Hudson Valley, dedicated to growing climate solutions. It would have been hosted in mid-July and if you are reading this, you would have likely been invited to participate or heard about it back in March. We wanted to build a small net zero dwelling for farm workers, learn about carbon positive building materials, passive heating and cooling, cook low-carbon food together, explore Wally Farms, it’s forests, wetlands and farm experiments and discuss the climate crisis.

The current Covid-19 pandemic forced me to rethink the original on-site summer workshop. Instead of sending out an invitation to participate in March, I stalled, tried to re-organize all the things I wanted to talk about during the workshop into online content, then stalled again. Reluctant to become a digital content producer overnight and uncertain how to rethink the complexity of talking about the climate crisis in the middle of a public health crisis and a massive movement to address systemic racism and the environmental inequities it continues to produce, I didn’t know, how to make a small net zero dwelling relevant. I believe there is no better way to learn than by doing and I hope to host in-person “Lab Sessions” at Wally Farms later this year. In the meantime, we are taking the project online and are excited to start sharing research and design in a weekly project diary, experimenting with different content and formats. One benefit to this format is that it can reach more people than the 15 or so workshop participants, we would have been able to accommodate in the Hudson Valley.

We invite students and (non-)professionals with interest in architecture, energy, environmental science, building technology, agriculture, biodiversity, food, climate and the Hudson Valley to follow us and actively participate in the discussion as we learn more about calculating embodied carbon in materials or how most zoning regulations make it hard to build “off-grid.”

Why Climate Action?

Climate Action is different from Climate Activism. Both are important, but I believe they do not always go hand in hand unfortunately. In March 2019 I was preparing a sign for the first global school strike for climate for my daughter Greta. She had asked me to write “Don’t Break Our Planet” on the sign. She had just turned three. After the event, she asked “Did we save it? Did we save the planet?” I didn’t dare to tell a three-year old: “No we didn’t. We just talked about it.” And while a three-year-old makes for good photos as a climate activist, it is not her job to save it. It is ours — “the grown-ups”.

The March 2019 school strike was part of a series of events that dramatically increased the urgency to act on climate change and gave us clear deadlines: 2030 to make significant strides, 2050 to create a world in which we absorb more carbon dioxide annually than we release into the atmosphere. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued a report in 2018 that limiting global warming to 1.5°C would require “rapid and far-reaching” transitions in the use of land, energy, industry, buildings, transport, and cities.” The report alarmingly communicated urgency, but it did not encourage action, because it doesn’t tell us how. In fact very little of the global discussion is about the “how?” or “how exactly?”

The IPCC reports and media discussion of the climate crisis leave us with images of icebergs melting, sea levels rising, wildfires, deforestation and projections of drought and displacement. The situation is dire, but the descriptions of it are distant -at least to a great majority of people, who contribute most to greenhouse gas emissions and they are abstract. None of these messages are encouraging us to act. In fact they make “action” seem equally distant and abstract, something that requires enormous political will and enormous amounts of money.

Project Drawdown, published in 2017, subtitled “the most comprehensive plan ever proposed to reverse global warming” is not actually a plan, but instead a comprehensive list of 100 solutions ranked by their potential impact globally. The list does not give us a roadmap of how to get to zero emissions, but it offers a start by describing what exactly contributes to greenhouse gas emissions or conversely to their absorption and it gives us a sense of scale estimating how much each of these solutions could contribute to “drawing down” -reducing greenhouse gas in the atmosphere. Who, before reading Project Drawdown knew that the single most effective strategy globally would be to phase out and properly dispose of HFC containing refrigerators and air conditioners? By focusing on greenhouse gas emissions produced by the systems and spaces of our daily lives it also moves us beyond the conversation of whether China or the US or Europe are the greatest source of emissions, but instead it highlights solutions organized by categories such as energy, food, land use, women and girls, buildings and cities, transport and materials in a global context. So of all these systems to act on, the Climate Action Lab is taking a look at buildings and the building industry.

As a society, and as professionals in the built environment, we need to talk a lot more about solutions, about taking action within our own field: Buildings account for 40% of all greenhouse gas emissions globally. Our projections for global population growth and the growth of cities is that we are adding more buildings to this world at the scale of one New York City every month. We need to take action and reduce the emissions from these buildings and in order to do that, we need a better understanding of the social, economic and ecological systems behind those emissions. We need to stop thinking about solar panels as the only solution and ask questions about what is actually consuming all that energy these solar panels will produce?

How is it possible that embodied energy (the energy it takes to make something) in construction material or really anything we consume is such a niche topic? How is it possible that we know so little about data centers and logistics, the spaces and networks that are critical in our interconnected lives? Now that we live more and more online during this pandemic, we seem to be still oblivious to poor real estate decisions, in fact even more so out of a desire to avoid density, and work and shop from home.

Well, how can a 400 square foot dwelling make a big difference? It cannot. The objective of the Climate Action Lab is to put the 400 square foot dwelling into a larger context. To use it as a vehicle to research, discuss and challenge the many scales of decision-making that lead to our enormous ecological footprint. From real estate markets to zoning regulations to global supply chains of materials to the very minute design and construction details that go into building an energy-efficient home. The 400 square foot dwelling is part of a multi-scalar system of production and consumption. Attempts to be “off the grid” do not change that. I hope that it can serve as some sort of prototype for small dwelling units, but even more so to spark conversation about our ecological footprint and how more information on how to “act” on climate change will lead to a different climate activism. One that complements global discussions and international COP meetings with local action and decision-making.

Next week, I want to talk about the carbon footprint of housing and some of the barriers to building smaller homes.

*Originally posted on Medium